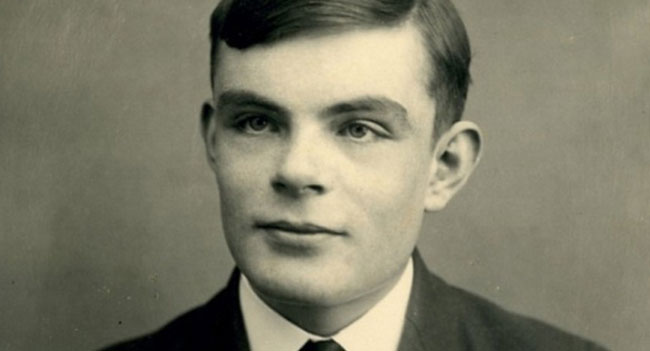

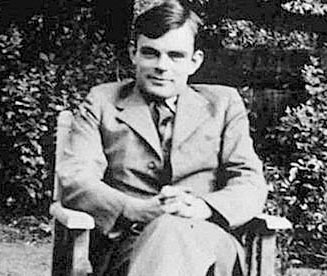

(1) A mathematician, logician, and cryptographer, Alan Mathison Turing is often considered to be the father of modern computer science. A shy, awkward man, Turing played a seminal role in the creation of computers. To be sure, many other people contributed, from mathematicians Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace in the 1830s to Herman Hollerith at the turn of the century. But it was Turing who made the critical conceptual breakthrough in a paper he wrote while in his 20s.

(2) Turing was born into the British upper middle class in 1912. Turing’s father, Julius Mathison Turing, was a member of the Indian civil service. Julius and his wife Ethel wanted Alan to be brought up in England, so they returned to Paddington, London, where Alan Turing was born on June 23, 1912. His father's civil service commission was still active, and during Turing's childhood years his parents travelled between Guildford, England and India, leaving their two sons to stay with friends in England, rather than risk their health in the British colony. Very early in life, Turing showed signs of the genius he was to display more prominently later. He was said to teach himself to read in three weeks, and showed an early affinity for numbers and puzzles.

(3) His parents enrolled him at St. Michael's, a day school, at the age of six. The headmistress recognized his genius early on, as did many of his subsequent educators. At the age of 14, he went on to Sherborne School in Dorset. Turing's natural inclination toward mathematics and science did not earn him respect with the teachers at Sherborne, a famous and expensive public school, whose definition of education placed more emphasis on the classics. His headmaster wrote to his parents: "I hope he will not fall between two schools. If he is to stay at Public School, he must aim at becoming educated. If he is to be solely a Scientific Specialist, he is wasting his time at a Public School". He was criticised for his handwriting, struggled at English, and even in mathematics he was too interested in his own ideas to produce solutions to problems using the methods taught by his teachers. Despite producing unconventional answers, Turing did win almost every possible mathematics prize while at Sherborne and continued to show remarkable ability in the studies he loved, solving advanced problems without having even studied elementary calculus.

(4) The event which was to greatly affect Turing throughout his life took place in 1928. He formed a close friendship with Christopher Morcom, a pupil in the year above him at school, and the two worked together on scientific ideas. Perhaps for the first time Turing was able to find someone with whom he could share his thoughts and ideas. However Morcom died in February 1930 and the experience was a shattering one to Turing. He had a premonition of Morcom's death at the very instant when he got ill and felt that this was something beyond what science could explain.

(5) The computer room at King's is now named after Turing, who became a student there in 1931 and a Fellow four years later. Due to his unwillingness to work as hard on his classical studies as on science and mathematics, Turing failed to win a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge, and went on to the college of his second choice, King's College, Cambridge. He graduated with a distinguished degree, and after that was elected a Fellow at King's. Then he moved on to Princeton University. It was during this time that he explored what was later called the “Turing Machine”.

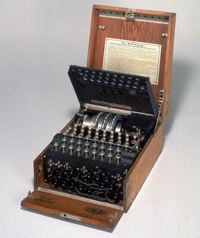

(6) During World War II, Turing used his knowledge and ideas in the Department of Communications in Great Britain. He used his mathematical skills to break German ciphers. The Enigma machines of the German navy were much harder to break as it was able to generate a constantly changing code but this was the type of challenge which Turing enjoyed. Turing contributed several insights into breaking the Enigma machine and was, for a time, head of the section responsible for reading German Naval signals. In 1945, Turing was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his wartime services.

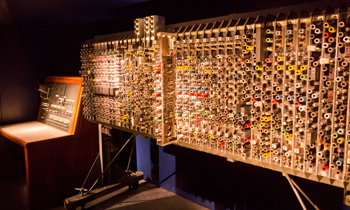

(7) After World War II, Turing worked for the National Physical Laboratory and continued his research into digital computers. Here he worked on developing the Automatic Computing Engine, one of the first steps at creating a true digital computer. Turing helped pioneer the concept of the digital computer. It was during this time that he began to explore the relationship between computers and nature. In 1950 he wrote a paper called “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”. This was one of the first times the concept of artificial intelligence was raised. Turing believed that machines could be created that would mimic the processes of the human brain. In his mind, there was nothing the brain could do that a well designed computer could not. As a part of his argument, he described devices already in existence that worked like parts of human body, such as television cameras and microphones. The Turing Machine that he envisioned is essentially the same as today’s multi–purpose computers.

(8) He described a machine that would read a series of ones and zeros from a tape. These ones and zeros described the steps that needed to be done to solve a particular problem or perform a certain task. The Turing Machine would read each of the steps and perform them in sequence, resulting in the proper answer. This concept was revolutionary for the time. Most computers in the 1950’s were designed for a particular purpose or a limited range of purposes. What Turing envisioned was a machine that could do anything, something that we take for granted today. He essentially described a machine which knew a few simple instructions. Making the computer perform a particular task was simply a matter of breaking the job down into a series of these simple instructions. This is identical to the process programmers go through today. He believed that an algorithm could be developed for any problem. The hard part was determining what the simple steps were and how to break down the larger problems.

(9) In 1950 he wrote a paper describing what is now known as the “Turing Test”. He proposed a bold measure for machine intelligence: If a person could hold a typed conversation with "somebody" else, not realizing that a computer was on the other end of the wire, then the machine could be deemed intelligent. The test consisted of a person asking questions via keyboard to both a person and an intelligent machine. He believed that if computer's answers could not be distinguished from those of the person after a reasonable amount of time, the machine was somewhat intelligent. This test has become a standard measure of the artificial intelligence community. Since 1990 an annual contest has sought a computer that can pass this "Turing Test." Nobody has yet taken the $100,000 purse. Turing would no doubt be delighted that engineers all over the world are still trying.

(10) Turing left the National Physical Laboratory before the completion of the Automatic Computing Engine and moved on to the University of Manchester. There he worked on the development of the Manchester Automatic Digital Machine (MADAM). He truly believed that machines would be created by the year 2000 that could replicate the human mind. He worked to create the operating manual for the MADAM.

(11) One major aspect of Turing’s life that often goes unnoticed is his work in biology. He worked from 1952 until his death on mathematical biology, specifically morphogenesis. He presented one paper on the subject called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis". Later papers went unpublished until 1992 when Collected Works of A.M. Turing were printed.

(12) In 1954, at 41, he died suddenly of cyanide1цианин poisoning, from eating a cyanide-poisoned apple. The apple itself was never tested for contamination with cyanide. It is interesting that this method of self-poisoning was similar to Turing's favourite film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs2гном. The official explanation was that it was a "moment of mental imbalance". But his mother said he used to experiment with household chemicals, trying to create new substances and became careless. Others claimed he was embarrassed about his sexuality.

(13) Whatever the reason for his death, Turing was truly one of the greatest forerunners in the field of computers leaving the world a permanent legacy. Computers have revolutionised so many aspects of our world that today it is hard to imagine life without them. But today’s computer scientists still refer to his papers. The concept of the algorithm lies at the heart of every computer program for any type of digital computer. It is very conceivable that his idea of thinking machines by the year 2000 is not so far from the truth.

(14) Since 1966, the Turing award has been given annually by the Association for Computing Machinery to a person for technical contributions to the computing community. It is widely considered to be equivalent of the Nobel Prize in the computing world.

Adapted from the Internet sites