(1) Norbert Wiener (26 November 1894 - 18 March 1964) was an American theoretical and applied mathematician. He was a pioneer in the study of noise processes, contributing work relevant to electronic engineering, electronic communication and control systems. Wiener is perhaps best known as the founder of cybernetics, a field that formalizes the notion of feedback and has implications1влияние for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, philosophy, and the organization of society.

(2) Norbert Wiener was the first child of Leo Wiener a Russian – Jewish immigrant and Bertha Kahn, of German – Jewish decent. Leo Wiener had a major influence on his son. He attended medical school at the University of Warsaw but was unhappy with the profession, so he went to Berlin where he began training as an engineer. This profession seemed only a little more interesting to him than the medical profession, and he immigrated to the United States. Throughout his education Leo was interested in mathematics that was a deep amateur interest to him all through his life, although he never used his mathematical skills in any jobs he held.

(3) Having arrived in New Orleans in 1880, Leo tried his hand at various jobs in factories and farms before becoming a school teacher in Kansas City. He progressed from being a language teacher in schools to becoming Professor of Modern Languages at the University of Missouri.

(4) Leo educated Norbert at home until 1903, except for a brief interlude when Norbert was 7 years of age. Thanks to his father's tutelage and his own abilities, Wiener became a child prodigy. Although Leo earned his living teaching German and Slavic languages, he read widely and accumulated a personal library from which the young Norbert benefited much. Leo also had ample ability in mathematics, and tutored his son in the subject until he left home. Having graduated from Ayer High School when he was 11 years old, Wiener entered Tufts College. He was awarded a BA in mathematics in 1909 at the age of 14, whereupon he began graduate studies in zoology at Harvard. In 1910 he transferred to Cornell to study philosophy. Having returned to Harvard next year, he still continued his philosophical studies. Back at Harvard, Wiener came under the influence of Edward Vermilye Huntington, whose mathematical interests ranged from axiomatic foundations to problems posed by engineering. Harvard awarded Wiener a Ph.D. in 1912, when he was a mere 18, for a dissertation on mathematical logic, supervised by Karl Schmidt.

(5) In 1914, Wiener travelled to Europe, to study under Bertrand Russell and G. H. Hardy at Cambridge University, and under David Hilbert and Edmund Landau at the University of Göttingen. In 1915-16, he taught philosophy at Harvard, then worked for General Electric and wrote for the Encyclopedia Americana. When World War I broke out, Oswald Veblen invited him to work on ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Thus Wiener the eventual pacifist wore a uniform in 1917-18. Living and working with other mathematicians strengthened and deepened his interest in mathematics. After the war, Wiener was unable to secure a position at Harvard because he was Jewish (despite his father being the first tenured Jew at Harvard)2не смотря на то, что его отец

был первым штатным сотрудником

еврейской национальности в

Гарварде, and was rejected for a position at the University of Melbourne. At W. F. Osgood's invitation, Wiener became an instructor in mathematics at MIT, where he spent the remainder of his career, rising to Professor. In 1926, Wiener returned to Europe as a Guggenheim scholar. He spent most of his time at Göttingen and with Hardy at Cambridge, working on Brownian motion, the Fourier integral, Dirichlet's problem, harmonic analysis, and the Tauberian theorems. Wiener's parents did not tell him that he was of Jewish ancestry. In 1926, his parents arranged his marriage to a German immigrant, Margaret Engemann, who was not Jewish; they had two daughters. Margaret was a Nazi sympathizer and did not keep that fact a secret.

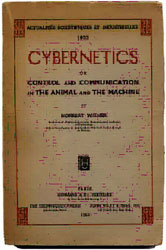

(6) During World War II, his work on the automatic aiming and firing of anti-aircraft guns3орудия с автоматической системой наведения огня led Wiener to communication theory and eventually to formulate cybernetics.

(7) After the war, his prominence helped MIT to recruit what was perhaps the world's first research team in cognitive science, made up of some of the brightest researchers in neuropsychology and the mathematics and biophysics of the nervous system, including Warren Sturgis McCulloch and Walter Pitts. These men went on to make pioneering contributions to computer science and artificial intelligence. Shortly after this painstakingly assembled research group was formed, Wiener suddenly and inexplicably broke off all contacts with its members.

(8) Speculation still flourishes as to why this split occurred; were the reasons professional, was his hypersensitive personality to blame, or did the split result from intrigues by his spouse Margaret? Whatever the reason, the split led to the premature end of one of the most promising scientific research teams of the era.

(9) Nevertheless, Wiener went on to break new ground in cybernetics, robotics, computer control, and automation. He freely shared his theories and findings, and generously credited the contributions of others. This stance4позиция, отношение resulted in his being well-disposed towards Soviet researchers and their findings, which placed him under regrettable suspicion during the Cold War. Wiener declined an invitation to join the Manhattan Project, and was arguably the most distinguished scientist to do so. After the war, he became increasingly concerned with what he saw as political interference in scientific research, and the militarization of science. His article "A Scientist Rebels" in the January 1947 issue of The Atlantic Monthly urged scientists to consider the ethical implications of their work. He was a strong advocate of automation to improve the standard of living, and to overcome economic underdevelopment. His ideas became influential in India; whose government he advised during the 1950s.

(10) After the war, he refused to accept any government funding or to work on military projects. The way Wiener's stance towards nuclear weapons and the Cold War contrasted with that of John von Neumann is the central theme of Heims’s book “John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener: From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death” (1980). Wiener’s vision of cybernetics had a powerful influence on later generations of scientists, and inspired research into the potential to extend human capabilities with interfaces to sophisticated electronics, such as the user interface studies conducted by the SAGE program. Wiener changed the way everyone thought about computer technology, influencing several later developers of the Internet, most notably J.C.R. Licklider.

(11) Having won the US National Medal of Science in 1964, he published one of his last books entitled “God and Golem, Inc.: A Comment on Certain Point Where Cybernetics Impinges on Religion.”

(12) Norbert Wiener died in Stockholm of a second heart attack at the age of 70.

Adapted from the Internet sites