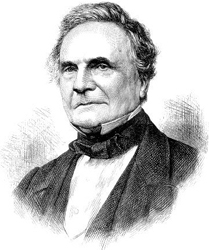

(1) British inventor Charles Babbage is one of the great paradoxes of computing history. Although he is often credited with developing the first "general-purpose computer," he never actually built any examples of his design. His steam-powered Analytical Engine, as it was called, would seem extremely primitive to us today, but in the 1830s, it was a groundbreaking design.

(2) Babbage was born in Teignmouth, Devonshire (UK) into a middle-class banking family, in December 1791. He followed an educational path typical for his age and status. His father’s money allowed Charles to receive instruction from several schools and tutors during the course of elementary education. At the age of eight he was sent to a country school to recover from a life-threatening fever with the strict instruction to the master not to press too much knowledge upon him. Perhaps this great idleness and a well-stocked library in the academy in Middlesex prompted his love of mathematics. Here he began to show a passion for mathematics but a dislike for the classics. On leaving the academy, he continued to study at home, having an Oxford tutor to bring him up to university level. He had read extensively in Leibniz, Lagrange, Simpson and was seriously disappointed in the mathematical instruction available at Trinity College in Cambridge. In response, he, John Hershel, George Peacock and several other friends formed the Analytical Society to try to bring the modern continental mathematics to Cambridge.

(3) Babbage and Herschel produced the first of the publications of the Analytical Society when they published Memoirs of the Analytical Society in 1813, a remarkably deep work when one realises that it was written by two undergraduates. They gave a history of the calculus, and of the Newton-Leibniz controversy. Surprisingly, in spite of being the top mathematician he failed to graduate with honours.

(4) As an active participant in the mathematical circles of the day, he founded the Analytical Society, the British Association for the Advancement of Science and the Royal Astronomical Society and served as Lucasian professor of mathematics at Cambridge. He also published a number of books on mathematics, statistics, and a variety of mechanical and industrial topics. His fascination with the mechanics was a lifelong interest. Rather than watch plays and operas with his society counterparts, he chose to go behind the scenes to view the trap doors, stage elevators, and other mechanisms of an 1800s theater.

(5) Babbage is without doubt the originator of the concepts behind the present day computer. The computation of logarithms had made him aware of the inaccuracy of human calculation around 1812. Once he wrote: "... I was sitting in the rooms of the Analytical Society, at Cambridge, my head leaning forward on the table in a kind of dreamy mood, with a table of logarithms lying open before me. Another member, coming into the room, and seeing me half asleep, called out, Well, Babbage, what are you dreaming about?" to which I replied "I am thinking that all these tables" (pointing to the logarithms) "might be calculated by machinery."

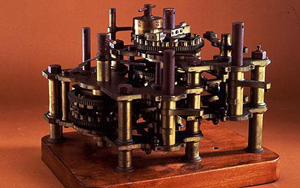

(6) Certainly Babbage did not follow up this idea at that time but in 1819, when his interests were turning towards astronomical instruments, his ideas became more precise and he formulated a plan to construct tables using the method of differences by mechanical means. Such a machine would be able to carry out complex operations using only the mechanism for addition. He completed a small difference engine in 1822. It was on 14 June 1822 when Babbage’s computing career began. He announced his invention in a paper Note on the application of machinery to the computation of astronomical and mathematical tables read to the Royal Astronomical Society. It would become his downfall as well.

(7) Although Babbage envisaged a machine capable of printing out the results it obtained, this was not done by the time the paper was written. An assistant had to write down the results obtained. Babbage illustrated what his small engine was capable of doing by calculating successive terms of the sequence n2 + n + 41.

(8) As he was convinced that a large difference engine could do the work undertaken by teams of people saving cost and being totally accurate, he sought public funds for the construction of a large difference engine. In 1823 Babbage received a gold medal from the Astronomical Society for his development of the difference engine and his initial grant for 1500 pounds. He began work on a large difference engine which he believed he could complete in three years. However the construction proceeded slower than had been expected. Over the next several decades, he designed the Difference Engine again and again, making each incarnation more efficient, more elegant and more compact than the one before, and leaving a trail of unfinished efforts in his creative wake.

(9) In 1834 Babbage published his most influential work On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, in which he proposed an early form of what today we call operational research. The same year was the one in which the work stopped on the difference engine. By that time the government had invested 17000 pounds into the project and Babbage had put 6000 pounds of his own money.

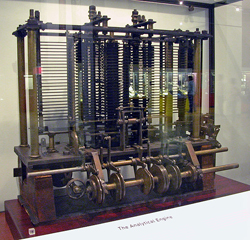

(10) By the 1840, Babbage had moved on to an even more ambitious machine that he called the Analytical Engine. It was never constructed either, but in theory, anyway, it represented a substantial advancement over the Difference Engine. A programmable machine with memory and a central processor, capable of looping and conditional branching, the Analytical Engine possessed many structural elements of the modern digital computer. But in 1842 funding for Babbage and his work stopped, the government decided not to proceed and stuck the incomplete Difference Engine in the Science Museum, where it still sits.

(11) Babbage's biographers have noted that the government failed to recognize the potential of Babbage's insights, the immense possibilities of his work, ignored the advice of the most reputable scientists and engineers, misunderstood his motives and the sacrifices he had made, and failed to protect him from the ridicule he suffered as a result of its failure. However, Babbage never gave up hope of building his Analytical Engine, he wrote;” ... if I survive some few years longer, the Analytical Engine will exist... ”. He applied once more for funding in 1851 but was turned down. He was reviled in the press and by the public for his careless spending of public funds and died in obscurity1умер в безвестности in October 1871.

(12) A classic curmudgeonly polymath who was known--with good reason—as "The Irascible Genius", Babbage was an inveterate, obsessive thinker, a mathematician with a penchant for engineering that led him, over the course of his long and colorful life, to invent such varied items as the ophthalmoscope, the cowcatcher found on the fronts of locomotives, the black-box recorder (for trains), a submarine automated by compressed air, a seismograph for measuring earthquakes, a "coronagraph" for generating artificial eclipses, a pen that drew dotted lines (for mapmaking), ergonomic paper (green ink on green paper), Babbage found, was easiest on the eyes), and a pair of shoes designed to let the wearer walk on water (Babbage nearly drowned when testing them, thus establishing that his considerable mental powers did not extend to working miracles).

(13) When he wasn't busy inventing, Babbage dabbled in cryptography, wrote books of social criticism, and raised insult to an art form. The irascible genius was known for his ability to alienate people, and honed his talent on everyone from the Royal Society (which he attacked in a scurrilous book on how governmental corruption was contributing to the decline of English science) to street musicians (who met Babbage's persistent efforts to silence them by playing loudly right outside his window).

(14) Dismissed as a crackpot2чокнутый during his own lifetime and subsequently forgotten by all but the most enthusiastic computer buffs and obsessive Victorianists, Babbage has been relegated to the footnotes of history, a curious example of a man whose ideas were too far ahead of his time to make sense. Babbage's reputation as a visionary and engineer was vindicated when several of the machines he designed, notably the second Difference Engine and its 2.5-tonne printer, were built by the London Science Museum to commemorate the 200th anniversary of his birth in 1991. They had not been built at the time he had lived, mainly due to lack of funds. It was subsequently proven that the critical tolerances required by his machines exceeded the metallurgy and technology available at the time. Built from his original plans, not only did they work, they worked exceptionally well. Modern scientists have stated that Babbage's Analytical Engine was also a viable model, although the limitations of Newtonian physics (upon which it was based) might have prevented its realization at the time.

Adapted from the Internet sites