(1) In a tree-lined park not far from Moscow’s Yaroslavl Highway sits a stone figure of a bearded man in a peasant-style robe. Behind him, glittering in the sunshine, a 12-story-high steel arrow blasts a cigar-shaped rocket high into the sky over the city. That’s how generations of Russians knew Konstantin Tsiolkovsky—a visionary thinker, standing at the very foundation of their country’s pioneering exploration of space. By the dawn of the Space Age in the 1950s, Tsiolkovsky’s name was recognized around the world, and he was mentioned alongside Galileo, Kepler, and Copernicus as one of the intellectual giants who furthered humanity’s expansion beyond Earth. Tsiolkovsky is the solitary genius who laid out the principles of space travel when the practical means of achieving it still lay far in the future. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky is called the Russian father of rocketry. Being a self-educated man, he developed insights into space travel and rocket science, earning him a place in history as one of the pioneers of astronautics.

(2) Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky was the fifth of 18 children born to an impoverished Polish immigrant on 17 September 1857. At the age of 10, he developed scarlet fever, and lost a significant portion of his hearing, an ailment that isolated him from his peers. By the age of 14, he had been suspended from school, having acquired only a few brief years of formal education.

(3) But the young man had a thirst for learning. His father arranged for him to visit Moscow when Tsiolkovsky was 16, where he took advantage of the freely available Chertkovskaya Library. He studied mathematics, physics, chemistry and mechanics. In Moscow, Tsiolkovsky met Nikolai Fedorov, an eccentric Russian philosopher whose theory of “cosmism” had a profound effect on young Kostya. Fedorov prophesied that progress in science would eventually allow humans to achieve immortality and even resurrect long-dead ancestors. The population would swell so much that humanity would have to spread across the universe.

(4) According to his biographers, these were the ideas that awakened Tsiolkovsky’s interest in reaching outer space. Around this time, he also discovered the novels of French science fiction and adventure writer Jules Verne, such as From the Earth to the Moon (1865), which inspired a whole generation of spaceflight pioneers. Unlike most of his contemporaries, however, Tsiolkovsky did more than simply marvel at Verne’s descriptions of fantastic journeys. He questioned their practicality. He understood that shooting spacecraft from a giant cannon, Verne’s method of reaching the moon, would inevitably kill its passengers due to the force of acceleration. Were there other, gentler ways of accomplishing the same thing?

(5) In September 1879, upon his return to Ryazan, Tsiolkovsky’s years of self-directed study paid off when he passed the exam to get a teacher’s certificate. Around that time he began drafting his first scientific works, and even built a small centrifuge to simulate different levels of gravity and test their effects on chickens.

(6) In January 1880, the Ministry of Education assigned 22-year-old Konstantin to teach arithmetic and geometry in the town of Borovsk. While in Borovsk, Tsiolkovsky experimented with physical processes, particularly the properties of gases, which gave him ideas for a theoretical work titled Svobodnoe Prostranstvo, or “Free Space.” Completed in 1883, it wasn’t published until 1956, long after his death. In it Tsiolkovsky made the first attempt in his decades-long effort to describe the meaning of the cosmos for humanity and the effects that vacuum and weightlessness would have on future space travelers.

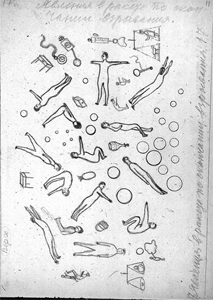

(7) The manuscript also contained a sketch considered to be one of Tsiolkovsky’s earliest depictions of a spacecraft. A simple drawing shows what spacesuited travelers in weightlessness, a cannon-like machine to propel the craft through the vacuum, and primitive gyroscopes to control the orientation of the ship in space look like. Also in Borovsk, Tsiolkovsky started drafting designs for airships, which, along with rocketry, would remain a passion for the rest of his life.

(8) In February 1892 he was promoted to another teaching position, in the provincial capital of Kaluga, which must have seemed a metropolis compared to Borovsk. Tsiolkovsky would remain in Kaluga until his death in 1935, and it was there that he created the monumental body of work that secured his place as a prophet of the Space Age. He started with a work of science fiction. In 1895, he published Grezy o Zemle i Nebe (Dreams of the Earth and Sky), which describes mankind’s settlement of space, complete with characters who mine asteroids and build orbital greenhouses.

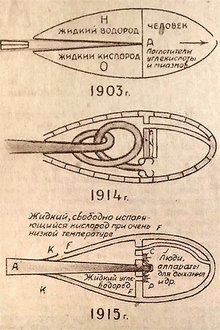

(9) In 1903, he published a manuscript titled “The Exploration of the World Space with Jet Propulsion Instruments” in Nauchnoe Obozrenie (Scientific Review) magazine. Today this work is universally recognized as the world’s first scientifically sound proposal to use rockets for exploring space. For decades afterward the work would stun readers with the completeness and level of detail with which Tsiolkovsky designed his spaceship. The mathematical relation he formulated between the changing mass of a rocket as it burns fuel, the velocity of exhaust gases, and the rocket’s final speed has since become known as Tsiolkovsky’s formula, and is considered one of the foundations of the science of astronautics.

(10) Amazingly, more than two decades before Robert Goddard launched the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket, Tsiolkovsky fueled his theoretical engine with a mix of liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen, the same combination used today on the space shuttle, and still considered the most efficient of chemical rocket propellants. Tsiolkovsky arrived at the combination with little hope of testing his theory. He never attempted to build a rocket engine, let alone a spaceship. His discoveries stemmed from a thorough grounding in physics and mathematics, an awareness of the latest achievements in technology (for example, James Dewar first liquefied hydrogen in 1898), and a gift for prediction.

(11) In the 1920s, Tsiolkovsky learned about the work of German space pioneer Hermann Oberth, who, working with no knowledge of Tsiolkovsky’s writing, published his key proposals for rocket-powered spaceflight in 1923. Tsiolkovsky wrote to Oberth, asserting his rights as the first to conceive of rocket flight as he deeply cared about his priority in the field. Ironically, it was Oberth who later helped make Tsiolkovsky’s name widely known in the West by publicizing his insights.

(12) In 1926, Tsiolkovsky published Plan for Space Exploration, a bold 16-step program whereby human civilization could outlive its dying sun and settle the universe. The scheme called for rocket-powered airplanes, the use of plants for life support, and solar radiation to grow food and supply energy. He predicted the need for spacefarers to use pressurized suits when leaving the spacecraft, and envisioned the construction of large orbital settlements. According to Tsiolkovsky, humans would colonize the asteroid belt, the solar system, and ultimately the galaxy.

(13) That work was followed three years later by Kosmicheskie Raketnye Poezda (The Space Rocket Trains), which advanced Tsiolkovsky’s earlier thoughts about multi-stage rockets. His calculations proved that building a rocket with separate stages, each of which would be jettisoned as it finished consuming its propellants, would allow a payload to be accelerated indefinitely through the vacuum.

(14) Tsiolkovsky’s publications are full of ideas that would later become common practice in aerospace engineering. He proposed using graphite rudders to steer a rocket in flight, cryogenic propellants to cool combustion chambers and nozzles, and pumps to drive propellant from storage tanks into the combustion chamber. He considered human factors as well—at the dawn of the Space Age, the first cosmonauts were amazed by Tsiolkovsky’s accurate descriptions of weightlessness.

(15) Shortly before his death, he wrote: “All my life I have dreamed that by my work mankind would at least be advanced a little.”Whether this wish came true is a matter of some debate. When mankind did in fact reach outer space, it was a Russian, Yuri Gagarin, who went first. But was it Tsiolkovsky’s ideas that got him there? The answer is a qualified yes. Despite the fact that his theories remained largely unknown in the West for decades, his influence on the first generation of Russian space engineers is unquestionable. Modern researchers credit Tsiolkovsky’s work with helping to form Glushko and Korolev’s views on space travel. The schoolteacher from Kaluga did in fact live to watch the early progress in rocketry made by Glushko, Korolev, and their colleagues in the 1930s. He consequently revised his estimates of how soon humanity would enter space. In a newspaper article published in July 1935, just a few months before his death, he wrote: “Unending work in recent times has shaken my pessimistic views: Techniques have been found that will give remarkable results within a few decades.”

(16) Tsiolkovsky died famous and respected in his native land at the age of 78 on 19 September 1935. In the years following the Bolshevik Revolution, he enjoyed the recognition and financial support of authorities anxious to tout the superiority of the Soviet system. His scientific works were widely published and popularized, the new government granted him a pension. Toward the end of his life Tsiolkovsky wrote, “My entire life consisted of musings, calculations, practical works and trials. Many questions remain unanswered, many works are incomplete or unpublished. The most important things still lie ahead.”

(17) Tsiolkovsky is remembered for believing in the dominance of humanity throughout space, also known as anthropocosmism. He had grand ideas about space industrialization and the exploitation of its resources. Tsiolkovsky has been honored since his death in 1935. A far side moon crater is named in his honor. In 1989 he was invested in the International Aerospace Hall of Fame. The Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in Kaluga, Russia, keeps the importance of his theoretical work before the public. In Russia, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky is called "the father of theoretical and applied cosmonautics."

Adapted from the Internet sites